Few years ago, Syria and Turkey received much international media and poltical attention due the Syrian civil war. The recent earthquake that took place in the two countries on February 6, 2023, has brought them back into the spotlight and showed that the little attention the Syrian crisis receives today in the international media does not indicate the resolution of Syria’s problems but rather that we have become, say, used to them.

The difficulties Syria has had to grapple with in its response to the Earthquake are rooted in its unresolved civil war with the opposition, the Kurds, and the government controlling different patches of a country isolated by means of sanctions from the world. Syria’s actual humanitarian crises with dead corpses buried under the rubble, refugees freezing under snow storms, and an economy gasping for air under sanctions calls on us to wonder if 2011 had to occur the way it did. This situation, now almost a decade after the 2011protests, raises the question if other roads could have been taken by Arabs.

Ideology, culture, religion, ethnicity, patriotism, and other non-material political motivations, despite their constant setbacks before the intermittent triumphs of their traditional material enemies, namely technocracy, pragmatism, and science, have played an important role in pushing the wheel of history forward just as they impeded it at times.

The division of the World today into a conservative East and a “progressive” West whose ways should be copied has become a self-evident “truth” to many though it can be challenged by contrasts such as the one between Arab secularism and Meloni’s imagined Christian Italy or the one between the 2011 North African demonstrators and France’s monarchists.

Now, a decade from the political upheavals that disturbed North Africa and the Middle East (MENA), the people of these regions stand at a crossroads between choices hard to figure out but seemingly easy to pin down to an answer or sometimes to a person by some Western and Arab media.

What is certain today is that most of the ideological choices that the region could offer during the last decade have been exhausted. Their exhaustion is rather due to the poor offer than the wrong demand. Since 2011, people have had their choices resitricted to the two poles of the Islamist and the secular oppositions to the pre-2011 governments in Tunisia and Egypt whose sudden access to power made them look more like political apprentices engrossed in cultural reductionism than leaders.

The consequent public debate over the reconstruction of these two countries in 2011 was a cultural one and the result was two societies fragmented along the lines of secularism v.s. Islamism. Islamism has had the chance to rule under different forms of government. In Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Sudan, Islamists had the chance to dominate the goverments of their countries. In Morocco, Algeria, Kuwait, Jordan, and Mubarak’s Egypt, they took part in governments that sometimes featured secular parties.

The record of Islamist rule is far from satisfying. Islamists’ obsession with cultural reductionism has been their biggest enemy. Restricting the remedy of social woes to a religious awakening is a logical fallacy- or rather a strategy- they share with the Western right wing. As the general public waited for technical answers to economic hardships, the post-2022 Islamists in Tunisia and Egypt focused on rallying public support to an agenda of cultural reform that targeted the two countries’ deep-rooted secular traditions.

The pre-2011 secular elites that had opposed the rule of what the Western media describe as “secular dictatorship” also have had the chance to take part in the process of rebuilding political institutions in Tunisia and Egypt. Yet, whether in office or in opposition, they have failed to bring a significant contribution to this process, one that translates into strong State institutions, the Rule of Law, and a strong economy that wards off the shadow of fear.

In Tunisia, the alliance of some leftist and progressive parties with the Islamists of Ennahdha has brought on them the wrath of their supporters besides the blame for the negative bill of the “dark decade,” as Tunians qualify it, of Islamist rule. Those who were not lured by the prestige of power have been blamed for failing to give serious suggestions.

History teaches that in times of reconstruction, nationalism, as policy rather than ideology is the answer to address the ails of a shattered national ego. In those early decades of the second half of the 20th century which followed the process of decolonization in the MENA which started in the first half of the 20th century, the Arab states witnessed the arrival of secular Arab nationalist leaders to power.

Arab nationalism, despite the benefits it has brought into the region is far from a rebirth. The earlier context of the Cold War that favored an alliance between Soviet and Arab nationalism is a is a little more than a bygone memory cheriched by the post-World War II generation in their description of a regretted welfare system. Welfare through state spending itself cannot be replicated in today’s global context with most Arab states in huge debt to foreign lenders.

In the earlier Cold War decades, State investments were the recipe needed to help the West rebuild an economy devastated by the events of the first half of the 20th century, mainly the 2 World Wars and the crisis of the 1930s. In the East, it was more needed to address these same problems exacerbated by centuries of colonization.

Another problem of Arab nationalism is ideological. It is one that resonates with the difficulties the Western left faces in order to convince Western workers it is fighting for them while appealing to an international worker who can live in the South and who is a potential passenger on board of a rag-tag boat illicitly crossing the Mediterranean to compete with European workers.

Islamism cannot offer a more satisfying response for it appeals to a transnational identity that consecrates the Conservative values the region already has. The Arab and Muslim identity of the region is obvious and those who deny it tend to be motivated by psychological and ideological inclinations rather than by their experience with the culture.

Sings of this identity manifest in the mutual intelligibility between the Asian and the Mediterranean Arabs, and in shared cultural and religious symbols, causes, and sympathies. It has manifested itself in the predominantly Arab solidarity with Syria even from the UAE whose leaders had previously supported the Islamist opposition during the Syrian civil war.

This identity was capitalized on by the Qatari prince Hamad Ben Tamim celebrating the goals of Arab teams and cheering to the Arab crowds with members of his family during the 2022 edition of the FIFA world cup. Strangely, Aljazeera, the Qatar-based widely viwed TV channel recently focused more on the devastation caused by the earthquake in Turkey rather than in Syria.

But obvious as it might be, this identity is too large to dodge religious, ethnic, racial, and political fragmentation. The nationalism that has not been tried in the Arab region is local nationalism. Whether translated in political projects or new social behaviors, local nationalism needs to be tried in the Arab world because Arab countries are undergoing a period of reconstruction in which they cannot rely on Pan-Arabism.

Nationalism at the national level not only avoids Pan-Arabism but also local ethnic nationalist distractions embodied in Kurdish and Amazigh nationalisms, for example.

Tunisia is among the few Arab countries that have had a nationalist experience, dating back to French colonialism, which forged nationalist sentiments among educated Tunisians. This sentiment was translated politically into a nationalist movement that led the national struggle against French colonialism.

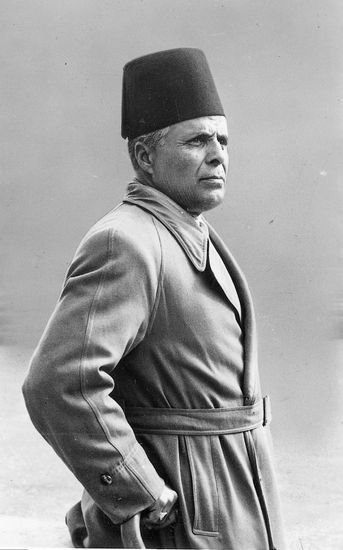

After independence, Habib Bourguiba, the leader of this movement became president of Tunisia and embarked on his nationalist policies that came later to be called “Bourguibism” characterized by strong commitment to Tunisian nationalism at the expense of Arab and Maghrebean nationalism.

In order to stand against foreign nationalisms, Bourguibism was a staunch enemy of Islamism by means of the secular reforms it implemented, which paved the way for the promotion of women’s rights and many civil liberties.

It is not the so-called “jasmine revolution’ which has bestowed on Tunisian women the liberties they take pride in today. It was rather Bourguiba’s nationalism.

History teaches that most regimes that face revolts do create a suitable ground for revolution due to their progressive concessions. It is no coincidence that the 2011 protests began in Tunisia and Egypt.

If nationalism in the West conjures up images of Nazism, protectionism, and right-wing conservatism, in the Arab world it brings memories of let-wing independentism, socialism, and in the Tunisian case, progressivism.

Even in the EU context, nationalism and transnational regional cooperation are not mutually exclusive. Italy’s Meloni has often appealed to a European and Western identity in her inflamed anti-immigrant speeches or in her commitment to the Ukraine side in their war against Russia.

The European Conservatives and Reformists Group, which incarnates the Conservative voice in the European Parliament, comprises Spain’s VOX, Meloni’s Fratelli D’Italia, and Sweden Democrats.